Background

Docker Swarm mode is built into the Docker Engine. Do not confuse Docker Swarm mode with Docker Classic Swarm which is no longer actively developed.

Docker’s native orchestrator is SwarmKit. It is used to deploy and run distributed, resilient, robust, and highly available applications in clusters on-premise or in the cloud. SwarmKit ensures secure applications by using a software defined network (SDN) to isolate containers.

The cluster management and orchestration features embedded in the Docker Engine are built using swarmkit. Swarmkit is a separate project which implements Docker’s orchestration layer and is used directly within Docker.

One of the key advantages of swarm services over standalone containers is that you can modify a service’s configuration, including the networks and volumes it is connected to, without the need to manually restart the service. Docker will update the configuration, stop the service tasks with the out of date configuration, and create new ones matching the desired configuration.

When Docker is running in swarm mode, you can still run standalone containers on any of the Docker hosts participating in the swarm, as well as swarm services. A key difference between standalone containers and swarm services is that only swarm managers can manage a swarm, while standalone containers can be started on any daemon. Docker daemons can participate in a swarm as managers, workers, or both.

In the same way that you can use Docker Compose to define and run containers, you can define and run Swarm service stacks.

Current versions of Docker include swarm mode for natively managing a cluster of Docker Engines called a swarm. Use the Docker CLI to create a swarm, deploy application services to a swarm, and manage swarm behavior.[1]

Architecture

A swarm consists of multiple Docker hosts which run in swarm mode and act as managers (to manage membership and delegation) and workers (which run swarm services).[2]

A given Docker host can be a manager, a worker, or perform both roles.

When you create a service, you define its optimal state (number of replicas, network and storage resources available to it, ports the service exposes to the outside world, and more).

Docker works to maintain that desired state.

For instance, if a worker node becomes unavailable, Docker schedules that node’s tasks on other nodes.

The architecture of a Docker Swarm consists of two main parts — a raft consensus group of an odd number of manager nodes, and a group of worker nodes that communicate with each other over a gossip network, also called the control plane.[2:1]

The manager nodes manage the swarm while the worker nodes execute the applications deployed into the swarm.

Each manager has a complete copy of the full state of the swarm in its local raft store.

Managers communicate with each other in a synchronous way and the raft stores are always in sync.

The workers, communicate with each other asynchronously for scalability reasons.

There can be hundreds if not thousands of worker nodes in a swarm.

Swarm nodes

A swarm is a collection of nodes.

A node as a physical computer or virtual machine (VM).

Install Docker on a node and this node becomes a Docker host.

To become a member of a Docker Swarm, a node must also be a Docker host.

A node in a Docker Swarm can have one of two roles. It can be a manager or it can be a worker.

Manager nodes do what their name implies; they manage the swarm. The worker nodes in turn execute application workload.

A manager node can also be a worker node and thus run application workload, although that is not recommended, especially if the swarm is a production system running mission critical applications.

Swarm Managers

Each Docker Swarm needs to have at least one manager node.

For high availability reasons we should have more than one manager node in a swarm. This is especially true for production or production-like environments.[2:2]

If we have more than one manager node then these nodes work together using the Raft consensus protocol.[2:3]

The Raft consensus protocol is a standard protocol that is often used when multiple entities need to work together and always need to agree with each other as to which activity to execute next.[2:4]

To work well, the Raft consensus protocol asks for an odd number of members in what is called the consensus group. Thus we should always have 1, 3, 5, 7, and so on manager nodes. In such a consensus group there is always a leader. In the case of Docker Swarm, the first node that starts the swarm initially becomes the leader. If the leader goes away then the remaining manager nodes elect a new leader. The other nodes in the consensus group are called followers.[2:5]

If the current leader node was shut down for maintenance reasons, the remaining manager nodes would elect a new leader. When the previous leader node goes back online it would then become a follower. The new leader remains the leader.[2:6]

All members of the consensus group communicate in a synchronous way with each other.

- Whenever the consensus group needs to make a decision, the leader asks all followers for agreement.

- If a majority of the manager nodes give a positive answer then the leader executes the task.

- If we have three manager nodes then at least one of the followers has to agree with the leader.

- If we have five manager nodes then at least two followers have to agree.[2:7]

Since all manager follower nodes have to communicate synchronously with the leader node to make a decision in the cluster, the decision-making process gets slower and slower the more manager nodes we have forming the consensus group.[2:8]

The recommendation of Docker is to use one manager for development, demo, or test environments. Use three manager nodes in small to medium size swarms, and use five managers in large to extra large swarms. To use more than five managers in a swarm is hardly ever justified.[2:9]

In addition to managing the swarm manager nodes are also responsible for maintaining the state of the swarm. This includes all the information about it—for example, how many nodes are in the swarm, what are the properties of each node, such as name or IP address. Also what containers are running on which node in the swarm and more. Data produced by the application services running in containers on the swarm, also called application data is not managed by the manager nodes.[2:10]

All the swarm state is stored in a high performance key-value store (kv-store) on each manager node. Each manager node stores a complete replica of the whole swarm state. This redundancy makes the swarm highly available. If a manager node goes down, the remaining managers all have the complete state at hand.[2:11]

If a new manager joins the consensus group then it synchronizes the swarm state with the existing members of the group until it has a complete replica. This replication is usually pretty fast in typical swarms but can take a while if the swarm is big and many applications are running on it.[2:12]

Swarm Workers

A swarm worker node is meant to host and run containers that contain the actual application services that will be running on our cluster. They are the workhorses of the swarm. In theory, a manager node can also be a worker. But this is not recommended on a production system.

Worker nodes communicate with each other over the “control plane”. They use the gossip protocol for their communication. This communication is asynchronous, which means that at any given time not all worker nodes must be in perfect sync.

What information do worker nodes exchange? It is mostly information that is needed for service discovery and routing, that is, information about which containers are running on with nodes and more.[2:13]

To make sure the gossiping scales well in a large swarm, each worker node only synchronizes its own state with three random neighbors.

Worker nodes are kind of passive. They never actively do something other than run the workloads that they get assigned by the manager nodes. The worker makes sure that it runs these workloads to the best of its capabilities. Further down in this chapter we will get to know more about exactly what workloads the worker nodes are assigned by the manager nodes.[2:14]

Stacks, services, and tasks

When using a Docker Swarm versus a single Docker host, there is a paradigm change. Instead of talking of individual containers that run processes, we are abstracting away to services that represent a set of replicas of each process.[2:15]

We also do not speak anymore of individual Docker hosts with well known names and IP addresses to which we deploy containers; we’ll now be referring to clusters of hosts to which we deploy services.[^!]

We don’t care about an individual host or node anymore. We don’t give it a meaningful name; each node rather becomes a number to us.[2:16]

We also don’t care about individual containers and where they are deployed anymore—we just care about having a desired state defined through a service.[2:17]

Services

A swarm service is an abstract thing. It is a description of the desired state of an application or application service that we want to run in a swarm. The swarm service is like a manifest describing such things as the:[2:18]

- Name of the service

- Image from which to create the containers

- Number of replicas to run

- Network(s) that the containers of the service are attached to

- Ports that should be mapped

Having this service manifest the swarm manager, then, makes sure that the described desired state is always reconciled if ever the actual state should deviate from it.[2:19]

So, if for example one instance of the service crashes, then the scheduler on the swarm manager schedules a new instance of the service on a node with free resources so that the desired state is reestablished.[2:20]

Tasks

A task is a running container which is part of a swarm service and managed by a swarm manager, as opposed to a standalone container.[3]

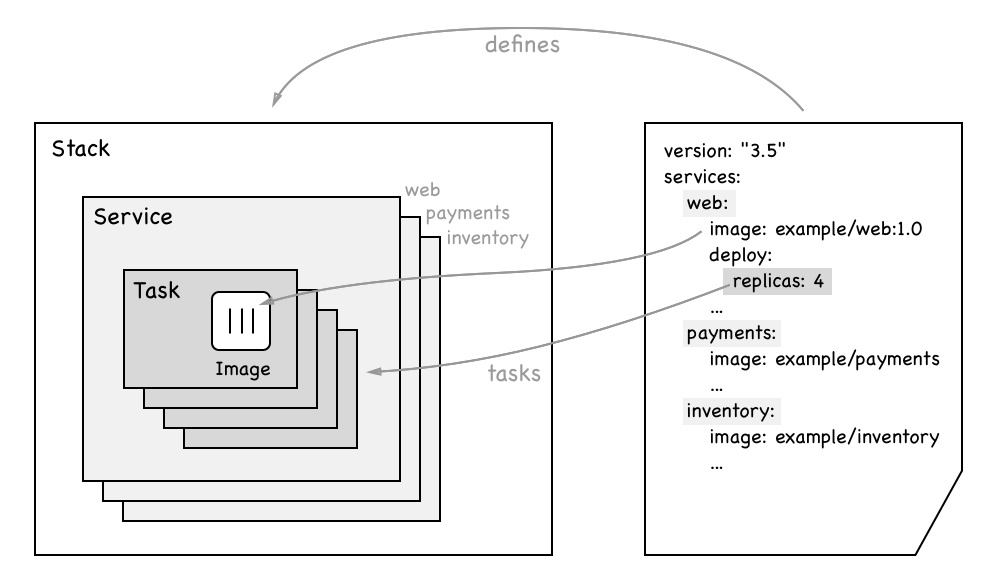

Each replica is represented by a task. In this regard, a swarm service contains a collection of tasks. On Docker Swarm, a task is the atomic unit of deployment. Each task of a service is deployed by the swarm scheduler to a worker node. The task contains all the necessary information that the worker node needs to run a container based off the image, which is part of the service description. Between a task and a container there is a one-to-one relation. The container is the instance that runs on the worker node, while the task is the description of this container as a part of a swarm service.[2:21]

Stacks

A stack is used to describe a collection of swarm services that are related, most probably because they are part of the same application.[2:22]

A stack describes an application that consists of one to many services that we want to run on the swarm.[2:23]

Typically, we describe a stack declaratively in a text file that is formatted using YAML and that uses the same syntax as the already-known Docker compose file.[2:24]

A stack is described in a stack file that uses similar syntax to a docker-compose file.[2:25]

The following image illustrates the relationship between stack, services, and tasks along with the content of a typical stack file.[2:26]